Introduction

Your PostgreSQL database keeps growing, even though the number of rows stays roughly the same. Disk usage climbs, queries slow down, and you wonder what the heck is happening.

It’s not a bug - it’s called bloat and it’s baked into the core design of Postgres.

To understand why it happens we have to follow the lifecycle of a row from the moment it’s written to a physical file to the moment it becomes “dead” space. This journey begins at the physical storage layer: Pages and Tuples.

Table of Contents

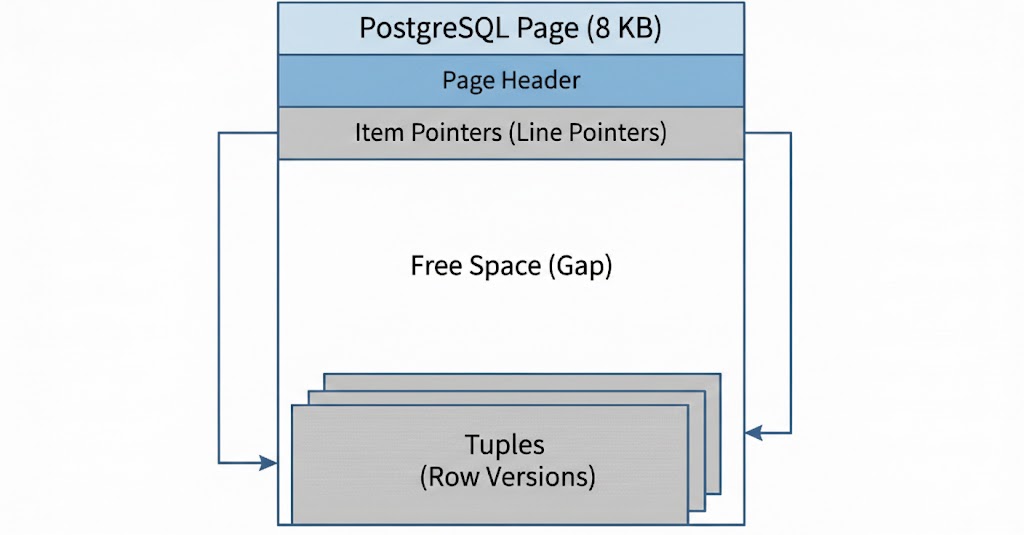

1. The Physical Layer: Pages and Tuples

Postgres stores tables as files on disk, divided into fixed-size pages (8 KB blocks). Inside each page are tuples - the physical versions of your rows. See below for a diagram of a Page:

Think of a page like a box with limited capacity. When you insert a row, Postgres writes a tuple into the first page with available space. If that page is full, it allocates a new page and appends it to the table file. Each tuple contains not just your data, but also metadata that Postgres uses to determine which transactions can see it (more on this in the MVCC section).

This page-based architecture has critical implications for how bloat develops:

Pages are the unit of I/O. Postgres doesn’t read individual rows—it reads entire 8 KB pages. Even if only one live tuple remains in a page, Postgres must load the full page into memory and scan past any dead tuples to find it

Pages don’t shrink. Once a page is allocated to a table, it stays part of that table file. Deleting rows frees space within pages but doesn’t return pages to the filesystem. Your table file can only grow or stay the same size through normal operations.

Multiple versions coexist. A single logical row in your application may correspond to several physical tuples spread across different pages. Each UPDATE creates a new tuple in a potentially different page, while the old tuple remains on disk.

But pages alone don’t cause bloat. The real culprit is how Postgres handles concurrent users: MVCC.

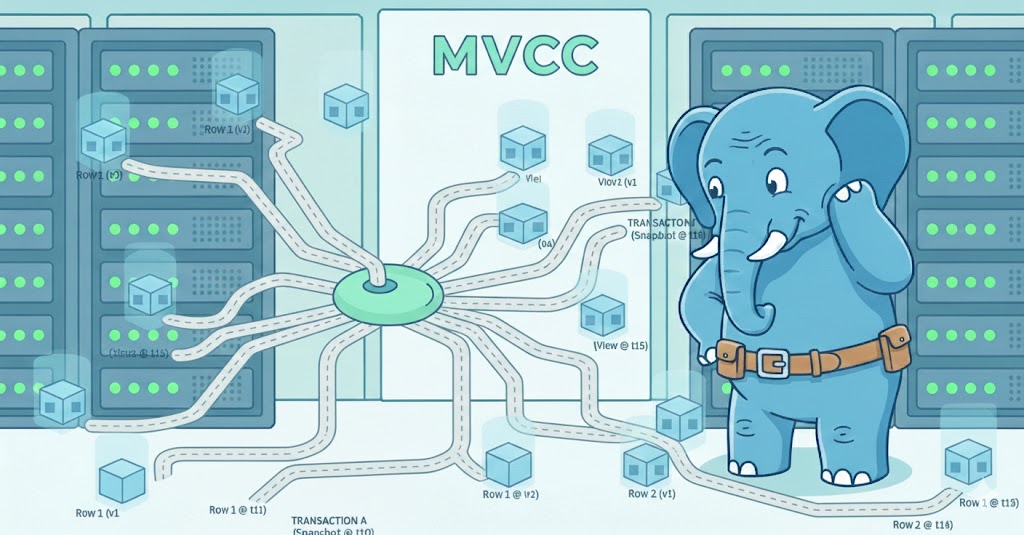

2. MVCC and Why Old Data Sticks Around

Postgres uses Multi-Version Concurrency Control (MVCC) so readers never block writers and writers never block readers. The mechanism is simple: instead of overwriting data in place, Postgres creates new versions.

Here’s what actually happens at the physical level:

UPDATEs create, they don’t modify. When you update a row, Postgres doesn’t find the existing tuple and change it. Instead, it writes a completely new tuple (often in a different page) containing the updated values. The old tuple stays exactly where it is on disk, but Postgres marks it as obsolete by setting its xmax field to the transaction ID that performed the update.

DELETEs don’t erase. When you delete a row, Postgres doesn’t remove the tuple from the page. It simply sets the tuple’s xmax to indicate which transaction deleted it. The data remains on disk, taking up space.

The result is tuple accumulation. Every update adds storage, every delete leaves behind a dead tuple. A table with frequent updates can accumulate dozens of tuple versions for each logical row, even though only one version is visible to new queries.

But why not just delete the old versions immediately? Because of concurrent transactions. When one transaction is updating a row, another transaction that started earlier might still be reading the old version. Postgres keeps old tuple versions around until it’s certain no transaction needs them anymore. Only then can the space be reclaimed.

These old tuple versions serve a purpose initially—they allow long-running transactions to see a consistent snapshot of the data. But once all transactions that could possibly need them have finished, these tuples become dead tuples: invisible to all queries, yet still consuming space in your pages.

This is where bloat emerges. Even though dead tuples won’t appear in query results, Postgres still has to:

- Load their pages from disk into memory

- Scan past them to find live tuples

- Keep them in your backup dumps

MVCC in Action

Let’s watch bloat happen in real-time. We’ll update a single row multiple times and see what Postgres actually does on disk.

We’ll start with a simple table using Postgres in docker:

$ docker run --name bloat-postgres -p 5432:5432 -e POSTGRES_PASSWORD=mypass -d postgres:18

$ docker exec -it bloat-postgres psql -U postgres

postgres=# CREATE TABLE users (id INT PRIMARY KEY, name TEXT, email TEXT);

CREATE TABLE

postgres=# INSERT INTO users VALUES (1, 'Alice', 'alice@wonderland.com');

INSERT 0 1

Now let’s update Alice’s email three times:

UPDATE users SET email = 'alice@newdomain.com' WHERE id = 1;

UPDATE users SET email = 'alice@company.com' WHERE id = 1;

UPDATE users SET email = 'alice@final.com' WHERE id = 1;

From your application’s perspective, you have one row. But Postgres now has four tuple versions of that row sitting on disk, the original plus three updates.

Every tuple in Postgres has hidden system columns that track its version:

- ctid: Physical location (page number, offset within page)

- xmin: Transaction ID that created this tuple

- xmax: Transaction ID that deleted/updated it (0 means it’s still current)

Let’s query these columns to see what’s really there:

SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, * FROM users;

-- you will see something similar to below:

postgres=# SELECT ctid, xmin, xmax, * FROM users;

ctid | xmin | xmax | id | name | email

-------+------+------+----+-------+-----------------

(0,4) | 768 | 0 | 1 | Alice | alice@final.com

Look at the ctid: (0,4) means page 0, tuple offset 4. We inserted one row and did three updates—so why is this the fourth tuple? Because each UPDATE created a new tuple version. Tuples 1, 2, and 3 are still on disk with xmax values marking them as superseded, but your query doesn’t see them; they’re dead.

Here’s what’s actually on disk:

Page 0, Tuple 1: [id=1, email='alice@wonderland.com', xmin=765, xmax=766] ← dead

Page 0, Tuple 2: [id=1, email='alice@newdomain.com', xmin=766, xmax=767] ← dead

Page 0, Tuple 3: [id=1, email='alice@company.com', xmin=767, xmax=768] ← dead

Page 0, Tuple 4: [id=1, email='alice@final.com', xmin=768, xmax=0] ← current

Each UPDATE created a new tuple and marked the old one as superseded by setting its xmax. The old tuples aren’t erased—they’re marked dead, waiting for cleanup.

We can see the dead tuple count in the table statistics:

postgres=# SELECT n_live_tup, n_dead_tup FROM pg_stat_user_tables WHERE relname = 'users';

n_live_tup | n_dead_tup

------------+------------

1 | 3

Three dead tuples from three updates. In a production table with millions of updates per day, this is how real bloat accumulates.

Dead tuples aren’t just wasted space, they force Postgres to do unnecessary work. Let’s prove it with a bigger example:

postgres=# CREATE TABLE products (id INT PRIMARY KEY, name TEXT, price NUMERIC);

-- Disable autovacuum for this example, we'll get to vacuuming later

postgres=# ALTER TABLE products SET (autovacuum_enabled = false);

postgres=# INSERT INTO products SELECT generate_series(1, 500), 'Product', 99.99;

INSERT 0 500

-- See how many pages we read with a full table

EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM products;

QUERY PLAN

----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Aggregate (cost=20.62..20.64 rows=1 width=8) (actual time=0.864..0.881 rows=1.00 loops=1)

Buffers: shared hit=4

-> Seq Scan on products (cost=0.00..18.50 rows=850 width=0) (actual time=0.196..0.332 rows=500.00 loops=1)

Buffers: shared hit=4

Note the Buffers: shared hit=4, Postgres read 4 pages to count 500 rows.

Now let’s delete 90% of the rows:

postgres=# DELETE FROM products WHERE id <= 450;

DELETE 450

postgres=# SELECT n_live_tup, n_dead_tup FROM pg_stat_user_tables WHERE relname = 'products';

n_live_tup | n_dead_tup

------------+------------

50 | 450

We now have only 50 live rows but 450 dead tuples. Let’s run the same query:

postgres=# EXPLAIN (ANALYZE, BUFFERS) SELECT COUNT(*) FROM products;

QUERY PLAN

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Aggregate (cost=4.62..4.63 rows=1 width=8) (actual time=0.723..0.771 rows=1.00 loops=1)

Buffers: shared hit=4

-> Seq Scan on products (cost=0.00..4.50 rows=50 width=0) (actual time=0.295..0.321 rows=50.00 loops=1)

Buffers: shared hit=4

Still reading 4 pages, even though we’re only returning 50 rows. Same I/O cost, but now 90% of that work is wasted scanning dead tuples to find the 50 live ones.

The more dead tuples per page, the more wasted I/O and CPU. A heavily bloated table might have pages that are 80% dead tuples—you’re reading 5x more data than necessary. This is why bloat isn’t just a disk space problem; it’s a performance problem.

But tables aren’t the only thing that bloats.

3. Index Bloat

There is a second, hidden cost to deletions and updates.

Since our products table has a PRIMARY KEY, Postgres automatically created an index for the id column. You might think that when you delete a row, Postgres just “erases” it from the index too. It doesn’t. The index entries pointing to dead tuples remain, taking up space.

Before the deletion, our index was 32 kB. Let’s check what it is now:

postgres=# SELECT pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('products_pkey')) AS index_size;

index_size

------------

32 kB

Still 32 kB - the index hasn’t shrunk despite having only 50 rows left. Unlike table bloat, index bloat requires REINDEX to reclaim space:

postgres=# REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY products_pkey;

REINDEX

postgres=# SELECT pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('products_pkey')) AS index_size;

index_size

------------

16 kB

The index dropped from 32 kB to 16 kB. REINDEX rebuilds the index from scratch, reading only the live tuples from the table.

REINDEX is faster but locks the table entirely, REINDEX INDEX CONCURRENTLY allows your application to keep running during the process, though it takes longer to completeAt this point, you might be thinking: if every update creates dead tuples, won’t databases just fill up with garbage? Yes - unless something cleans them up. Postgres’s answer is VACUUM, a background process that reclaims dead tuple space. But VACUUM comes with tradeoffs and quirks you need to understand. Let’s see it in action:

4. VACUUM

VACUUM is Postgres’s garbage collector. It scans tables for dead tuples and marks their space as reusable for future inserts and updates.

Let’s see it clean up our bloated users table:

postgres=# SELECT n_live_tup, n_dead_tup FROM pg_stat_user_tables WHERE relname = 'users';

n_live_tup | n_dead_tup

------------+------------

1 | 3

postgres=# VACUUM users;

VACUUM

postgres=# SELECT n_live_tup, n_dead_tup FROM pg_stat_user_tables WHERE relname = 'users';

n_live_tup | n_dead_tup

------------+------------

1 | 0

Three dead tuples gone. But here’s the catch:

postgres=# SELECT pg_size_pretty(pg_relation_size('users'));

pg_size_pretty

----------------

8192 bytes

One row, one page (8 KB). The dead tuples are gone, but the space they occupied is now free space inside that page—not returned to the operating system.

VACUUM FULL: The Nuclear Option

If you need to actually shrink the table file, there’s VACUUM FULL. It rewrites the entire table, packing live tuples into fresh pages and releasing unused pages back to the filesystem.

postgres=# VACUUM FULL users;

VACUUM

Autovacuum: The Background Worker

You don’t have to run VACUUM manually. Postgres has autovacuum, a background process that monitors tables and vacuums them automatically when dead tuples accumulate past a threshold.

By default, autovacuum triggers when:

- Dead tuples exceed 20% of live tuples + 50 rows

To see this we can query the pg_settings table:

postgres=# SELECT name, setting

FROM pg_settings

WHERE name IN ('autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor', 'autovacuum_vacuum_threshold');

name | setting

--------------------------------+---------

autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor | 0.2

autovacuum_vacuum_threshold | 50

For a table with 10,000 rows, that’s roughly 2,050 dead tuples before autovacuum kicks in. For a small table 20% is good enough but for a large table you probably want to tune these settings. Here’s how to do it:

postgres=# ALTER TABLE users SET (

autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor = 0,

autovacuum_vacuum_threshold = 50000

);

-- Check the new settings for that table

SELECT relname, reloptions

FROM pg_class

WHERE relname = 'products';

You can check when autovacuum last ran:

postgres=# SELECT relname, last_autovacuum, last_autoanalyze

FROM pg_stat_user_tables

WHERE relname = 'users';

relname | last_autovacuum | last_autoanalyze

---------+-------------------------------+-------------------------------

users | 2026-02-04 14:32:17.123456+00 | 2026-02-04 14:32:17.234567+00

Autovacuum works well for most workloads. But it has limits.

When VACUUM Can’t Keep Up

Autovacuum runs in the background, throttled to avoid impacting your queries. Under heavy write loads, dead tuples can accumulate faster than autovacuum cleans them. The result: bloat grows despite autovacuum running.

Common scenarios where this happens:

High-throughput updates. A table updated thousands of times per second can outpace the default autovacuum settings. You may need to tune autovacuum_vacuum_cost_delay and autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor for hot tables.

Long-running transactions. Remember how MVCC keeps old tuple versions for concurrent readers? A transaction that stays open for hours prevents VACUUM from cleaning any tuple that transaction might need to see. One forgotten BEGIN without a COMMIT can bloat your entire database.

-- Find long-running transactions

SELECT pid, age(clock_timestamp(), xact_start), query

FROM pg_stat_activity

WHERE state != 'idle'

ORDER BY xact_start;

Replica lag with hot standby feedback. If you’re streaming to a replica with hot_standby_feedback = on, the replica can hold back the primary’s VACUUM. Queries on the replica prevent cleanup on the primary.

Understanding these edge cases is half the battle. VACUUM works well when given the chance, but it needs help: short transactions, tuned thresholds for hot tables, and awareness of replica interactions. With that foundation in place, let’s recap what we’ve learned.

5. Takeaways

So how worried should you be about bloat? Probably not that much. Bloat is something that comes with Postgres. Bloat is only a problem if it’s causing other problems, like bad read latency, high (expensive) disk usage or high IOPS. Next question how much bloat is too much? That’s a judgment call and it depends on your workload. But the rule of thumb is: the bigger your database the less bloat you should accept. For lage databases > 40-100+ GB no more that 20% dead tuples - you can find out the percentage by running this query for example

If you do have a large database and issues with bloat the best way to deal with bloated tables is tuning autovacuum:

autovacuum_vacuum_scale_factor- as previously mentioned, default is 20% and can be set much lowerautovacuum_vacuum_threshold- default is 50 dead tuples and if you know your workload well you can setautovacuum_vacuum_scale_factorto 0 and set this to a higher valueautovacum_max_workers- default is 3 and can be set to a higher value. Checkpg_stat_progress_vacuumto see how many autovacuum workers are running. Increase if always at max