Concurrency in Go - Fundamentals

In this post we will delve into the fundamentals of Go’s concurrency features, the target audience are readers familiar with the language; however no prior knowledge of concurrency is required.

In this post we will talk about:

- brief discussion of Go’s concurrency features

- goroutines

- WaitGroup:s (from the sync package)

- Mutex (also from sync package)

- channels (buffered & unbuffered)

There’s definitely a lot more important subjects to cover but these are the basics that are vital to grasp.

Concurrency in Go

Without going into too much theory I would say that goroutines are at the core of concurrency in Go. Goroutines are user-space threads which are similar to kernel threads managed by the OS but instead managed entirely by the Go runtime. The reason for this is that user-space threads managed by the Go runtime are lighter-weight and cheaper than kernel threads. Also smaller memory footprint: initial goroutine stack = 2kb, default thread stack = 8kb

Go is pretty unique in that concurrency is a first-class citizen in the language, you don’t need to download 100 dependencies or learn a framework to be able to write effective concurrent programs; everything you need is included in the standard library.

Let’s move on by exploring goroutines

Goroutines

Goroutines is a function that is running concurrently, just put the keyworkd go in front of a function to make it run concurrently, example:

The only interesting part in this simple example is the order of the print’s, running this example will output:

$ go run main.go

Init

End

hello concurrency

The printer function is not running synchronous since we put the go keyword in front of it. You’ve might noticed the time.Sleep at line 16, lets delete that line and run the program again! Now the output is the following:

$ go run main.go

Init

End

Huh? Our printer function did not print it’s message… If you are not familiar with concurrency before this might seem a bit odd, however we just need to understand how our programs code execution works.

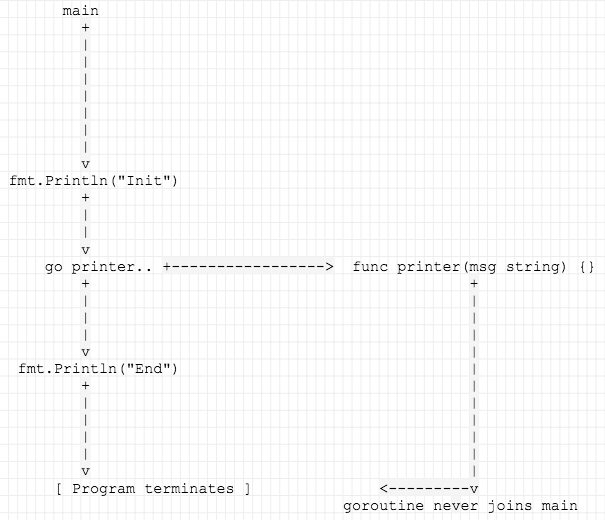

Go follows a model of concurrency called the fork-join model. This means that our program can split into it’s own execution branch to be run concurrently with its main branch. At some point in the future, the two branches of execution will be joined together again. Let’s try to visually understand what is happening here:

We can clearly see that at go printer… the code execution flow branches off into its side branch while the main branch continues to run. After we print End the main branch (the program) terminates so our side branch never gets time to execute. What we need to do here is to wait for the side branch to finish it’s execution, join it in the main branch and then we can continue. Let’s use WaitGroup from the sync package to help us with that.

WaitGroup

Think of WaitGroup as a mechanism to fire off concurrent operations, let them do work and then wait for them to finish. The usage of WaitGroup is primarily when you don’t really need to know the result (example, fire off lots of http POSTs) or you have some other means to collect the resource (for example with channels which I will cover further on). Let’s look at a trivial example below (I’ll comment each number in the code snippet below):

- This is our string slice with greek philosophers that we will print concurrently

- Here we declare a WaitGroup called wg

- For each element in the greeks slice we make a call to wg.Add(1) - wg.Add() adds to the WaitGroup counter. We then call the printer func concurenctly passing a pointer of wg

- In the printer func we use defer wg.Done() meaning if the WaitGroup counter was 2 it’s now 1

- wg.Wait() blocks execution of the main branch of our program until the counter reaches zero

Try to run the program a couple of times to see that the output will differ in order each time.

Concurrency Gotcha #1

Instead of calling a separate func in our example above and passing a pointer of the WaitGroup you can use an anonymous function in the range loop which is an common pattern, this brings us to a gotcha shown below. Can you spot the problem?

The output of our program is the following

$ go run main.go

Init

democritus

democritus

democritus

democritus

democritus

democritus

End

Pretty strange huh? In all fairness it’s pretty tricky to spot the error; what happens here is that there’s a high probability that the loop may exit before the goroutine begins, this means that the variable ph falls out of scope. But we actually got something printed out, why is that? Well, the go runtime knows that the ph variable is still being held and therefore will grab the last reference of that which are on the heap so that the goroutine can continue to access it.

A correct implementation would look like:

The trick here is that we need to pass a copy of ph to our anonymous func and thus making sure the goroutine will work on the data from the iteration of the loop:

Examples up to this point has been very hello world-ish so let’s make a program that actually does something remotely useful. The program below does the following things: concurrently http get’s and collect the status code in a map, we are using WaitGroup as before

This looks pretty straight forward, ….. But actually there’s a problem with this implementation which brings us to another concurrency gotcha; this code introduces a data race.

Concurrency Gotcha #2 - data race

So what’s a data race? A data race occurs when two or more goroutines access the same variable concurrently and at least one of the accesses is a write, this could lead to memory corruptions and crashes. It also makes the code unpredictable and hard to debug (potentially we can get different results each time the code is run).

But why did we get a data race? Simply put; maps are not thread-safe! To verify this we can use the built-in tool -race to test our code:

$ go run -race main.go

==================

WARNING: DATA RACE

Write at 0x00c000096cc0 by goroutine 9:

runtime.mapassign_faststr()

...

Previous write at 0x00c000096cc0 by goroutine 6:

runtime.mapassign_faststr()

...

Found 1 data race(s)

exit status 66

Ouch! There are several ways we can fix this, for example with channels which I will cover shortly. Another way to fix this would be if we could protect our map but still run things concurrently; for this we use something called mutex

Mutex

If you have a background in C/C++ mutex are probably familiar to you and they are similarly implemented in Go. Mutex stands for “mutual exclusion” and is a way to guard critical sections in your code from concurrent operations. To fix our data race from previous example we just need to put Lock() before the map operation and then Unlock() after the map operation has completed. Example below:

var wg sync.WaitGroup

var mu sync.Mutex

for _, url := range urls {

wg.Add(1)

go func(url string) {

defer wg.Done()

resp, err := http.Get(url)

if err != nil {

fmt.Errorf("url was error: %v", err)

}

mu.Lock()

respStatus[url] = resp.StatusCode

mu.Unlock()

}(url)

}

wg.Wait()Try to run this program with go run -race main.go and you will see that the data race warnings are gone!

Using Channels

You can think of channels as concurrency safe containers, you associate any data type with them (int, string, map, struct and so on). Channels are ideal when you want to communicate information between goroutines. This is how you declare a channel that will hold string

stream = make(chan string)You can define if the channel can only read or only write using the arrow character:

// channel can both send and receive

stream = make(chan string)

// channel can only read

stream = make(chan<- string)

// channel can only send

stream = make(chan-> string)Channel comes in two flavors:

- buffered channels

- unbuffered channels

Unbuffered channels are declared without a size (as example above) while buffered channels are declared with a fixed size, like so:

// buffered channel of strings buffering up to 2 values

stream = make(chan string, 2)The difference initially seems trivial but there is a important implication in how they operate;

- unbuffered channel: a send operation on an unbuffered channel blocks the sending goroutine until another goroutine executes a receive on the same channel, now both goroutines may continue

- unbuffered channel: if the receive operation was triggered first, the receiving goroutine is blocked until another goroutine performs a send on the same channel

- buffered channel: send operation inserts element in the buffer/queue while a receive operation removes the element from the channel. If the channel is at maximum capacity the send operation blocks until space is “freed” by another goroutine’s receive.

- buffered channel: if the buffer/queue is empty a receive oepration blocks until a value is sent by another goroutine

Let’s try to visualize these differences with some code examples:

From what we’ve just learned on an unbuffered channel we should do the send and receive operation in different goroutines to avoid a deadlock, below is a simple demonstration of how to do this:

func main() {

message := make(chan string)

// we need to execute the send operation in a separate goroutine

// as it would otherwise block the main goroutine

go func() {

message <- "ping"

}()

// execution blocks here until we receive something on channel message

msg := <-message

fmt.Println(msg)

}Buffered channel does not block except when the channel is full, so we can do the send and receive operation in the same goroutine. However this example sends 3 elements on a channel with capacity of 2, thus our program will result in an deadlock:

func main() {

// channel with capacity of 2

message := make(chan string, 2)

message <- "ping 1"

message <- "ping 2"

// at third element our channel is full thus our

// program will block here and terminate the program with an deadlock error

message <- "ping 3"

fmt.Println(<-message)

fmt.Println(<-message)

fmt.Println(<-message)

}This brings us to another concurrency gotcha: a deadlock!

Concurrency Gotcha #3 - deadlock

A deadlock manifests itself when a program with concurrent processes are waiting one one another. In this state, the program will never recover. The Go compiler will notice this error on compiletime and will give us a warning and refuse to compile the program. Trying to run this program above will result in the following error:

$ go run main.go

fatal error: all goroutines are asleep - deadlock!

goroutine 1 [chan send]:

main.main()

.../main.go:13 +0x9b

exit status 2

To make this code work we must unblock send operation from another goroutine, in the example below we do the send operation in a separate goroutine, it will block at element 3, but because the receive operation executes in a another goroutine the code will unblock:

func main() {

// channel with capacity of 2

message := make(chan string, 2)

go func() {

message <- "ping 1"

message <- "ping 2"

message <- "ping 3"

}()

fmt.Println(<-message)

fmt.Println(<-message)

fmt.Println(<-message)

}Closing Channels

A channel is not a resource like a file or tcp connection that needs to be closed after use to free up resources, they can be left open infinitely. However we have the choice of closing them. Doing so indicates that no more value will be sent on the channel. This is useful if we want to avoid a deadlock and move on with our execution logic or communicate with other channels to return.

A contrived but telling example is shown below. Here we create a buffered channel of type person, after writing to the channel we just want to iterate over the message without receiving from it. In normal cases this would result in a deadlock but since we closed the channel we’ve indicated that no more values can be sent to the channel.

type person struct {

Name string

Age int

}

func main() {

message := make(chan person, 3)

message <- person{Name: "ping 1", Age: 1}

message <- person{Name: "ping 2", Age: 2}

close(message)

for element := range message {

fmt.Printf("Age plus one is: %d\n", element.Age+1)

}

}Given what we learned so far of channel, let’s try to rewrite our concurrent urlfetcher program to using channels instead of mutex/shared memory. An example program is outlined below, I’ll explain the flow based on the comments:

- We create 2 channels and a WaitGroup. The WaitGroup is used to wait for producer goroutines to finish

- We loop each element in the url slice and starts a new producer goroutine for each one, making all http get:s concurrently

- The producer goroutine makes the http request and produces jobs for the consume goroutine

- The consumer goroutine collects all results

- Here we wait for the producer goroutines to finish, then we close the channel. Last we send done to signal to the consumer goroutine to end

Notice here that the producer function and the consumer functions are totally decoupled, they are using the urlChan channel to communicate, not by sharing memory. This pattern shown above are called Producer-Consumer pattern (in this case; multiple producers and one consumer)